The most famous painting of Benjamin Franklin's lightning experiment has the Founding Father surrounded by small cherubs — angelic children.

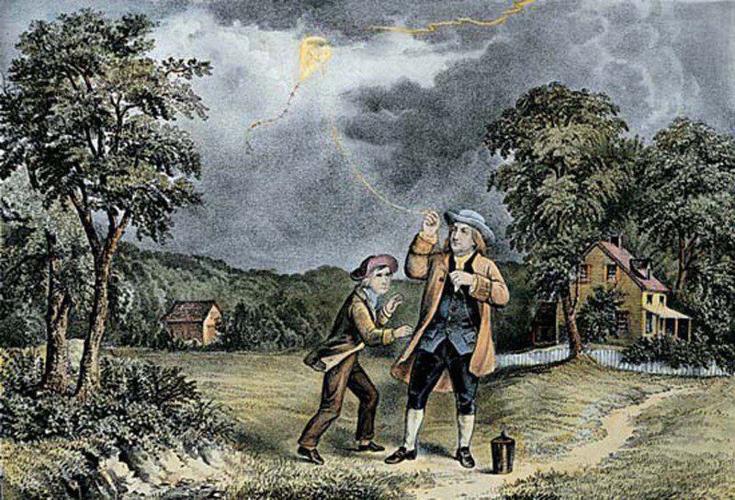

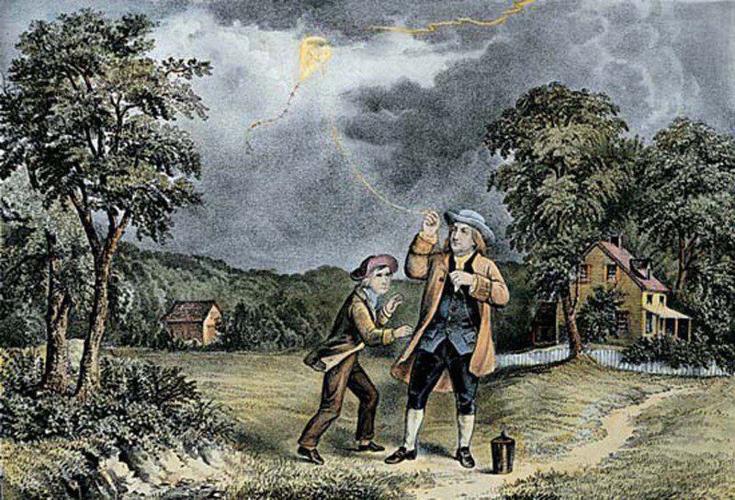

Other related paintings and etchings often depict Franklin with a child closer to his heart. Especially a 19th century print by Currier and Ives, depicting Benjamin Franklin and his young son luring lightning from the sky.

But there is a specter darker than thunder clouds looming in the illustrations.

Franklin looks like a wild, old fisherman baiting the clouds with a kite and a key. The boy watches his father and/or the skies incredulously as lightning dances above them.

Franklin and his son, William, and the lightning seem the stuff of folklore, similar to some Americanized Greek myth of a man and son daring Zeus then cursed for the arrogance of their folly.

But it is true.

There's some contention about the exact date when the experiment occurred, according to Walter Isaacson in his book, "Benjamin Franklin: An American Life," but most accounts agree Franklin seeded the skies for lightning in 1752.

Unlike the paintings of the familiar revolutionary wise man and small lad, Franklin was only 46, while William was not a small boy but a young man of 21.

The experiment led to the development of life-saving lightning rods attached to buildings and secured the international fame of Benjamin Franklin.

But like some mythical curse, despite the familial bonds depicted in the lightning art created decades after the experiment and even after Franklin's death, Benjamin and William were destined for trouble.

Not because of the kite experiment but because of the lightning rod of controversy of being on different sides of the American Revolution.

William was born in 1728 or 1729 from a relationship out of wedlock. Franklin never discussed the identity of William's mother, not even in his famed autobiography, likely for the sake of his son, but he fully claimed William and raised him in his household.

William was born just prior to Franklin marrying Deborah Read Rogers, who would bear Benjamin two more children.

"William became at once a part of the family, and his father doted on him," writes Edmund S. Morgan in his book, "Benjamin Franklin." "... Within his own family (Benjamin) was most obviously and most demonstrably fond of his son William, who became his closest confidant ..."

As a teenager, William accompanied his father on Benjamin's inspections along the Pennsylvania frontier, according to Edwin S. Gaustad in "Benjamin Franklin."

In 1757, when the Pennsylvania Assembly wanted to negotiate taxes and local rights, it sent Franklin to England. Franklin took William, then in his late 20s, with him.

They housed together and sought to fit into English society.

"Franklin and son imitated the fashions of London, buying new clothing, new knee buckles, and appropriate stationary," Gaustad writes. "'Everything about us pretty genteel,' the satisfied father noted."

Father and son traveled to northern England, Scotland and the Netherlands. They watched the coronation of King George III.

Yet, as Franklin worked often with little success in representing more American colonies and negotiating in an increasingly troubled atmosphere for colonial rights, William fit into British life better than his father.

Franklin returned to Pennsylvania. William stayed in England. He married well and was appointed royal governor of New Jersey, a success that would lead to trouble with his father.

For as William became a royal appointee, Franklin began questioning the American connection to Britain.

"A cloud was coming over the horizon, and there was no lightning rod to defuse its emotional charge," Isaacson writes. "The first signs of the tension that would develop between father and son came when Franklin decided to sail from England without him on Aug. 24, 1762 – the very day the news of William's pending appointment appeared in the papers and less than two weeks before his scheduled wedding."

"... Indeed, it meant that William, then about 31, would have a station in life higher than his father's, one that would likely reinforce his son's unattractive tendency to adopt elitist airs and pretenses."

The governorship then the push for American independence set the stage for the eventual split between father and son.

By the 1770s, Franklin had reluctantly then fully embraced being an Independence man. He urged his son to join him in seeking American independence. William refused. He would remain loyal to the king and England and remain the governor of New Jersey.

"Away from his father, (William) had grown into a man of his own, as convinced of the correctness of his principles as his father was of his principles, and as stubborn in defending them," H.W. Brands writes in "The First American." "The apple had fallen close to the tree in regard of character, if not of politics."

William was deemed an enemy of the Revolution. He was arrested "as a virulent enemy to this country, and a person that may prove dangerous." He was taken into custody and placed under the watch of American authorities.

"Franklin lifted no finger on behalf of his son," Brands writes. He sent $60 to William's wife but "he would not forgive William. Steeling his heart, he left him to his fate."

Franklin was angry that his son would not follow him but he also worried that any effort to help William would cause other Founders to question his loyalty to the American cause.

Though a famed publisher and writer, Franklin ceded writing the Declaration of Independence to Thomas Jefferson because he knew some Americans did not trust him because of William's loyalty to England.

Eventually, William would be sent to live the rest of his life in Britain, forever estranged from Franklin and America.

Franklin wrote his son years later.

"Indeed, nothing has ever hurt me so much and affected me with such keen Sensations, as to find myself deserted in my old Age by my only Son, and not only deserted but taking up Arms against me, in a Cause wherein my good Fame, Fortune and Life were all at Stake."

William claimed he had a duty as a royal governor but as Gaustad notes, "Perhaps, Franklin replied, but there was a higher duty than that: of a son to his father."

Other related paintings and etchings often depict Franklin with a child closer to his heart. Especially a 19th century print by Currier and Ives, depicting Benjamin Franklin and his young son luring lightning from the sky.

But there is a specter darker than thunder clouds looming in the illustrations.

Franklin looks like a wild, old fisherman baiting the clouds with a kite and a key. The boy watches his father and/or the skies incredulously as lightning dances above them.

Franklin and his son, William, and the lightning seem the stuff of folklore, similar to some Americanized Greek myth of a man and son daring Zeus then cursed for the arrogance of their folly.

But it is true.

There's some contention about the exact date when the experiment occurred, according to Walter Isaacson in his book, "Benjamin Franklin: An American Life," but most accounts agree Franklin seeded the skies for lightning in 1752.

Unlike the paintings of the familiar revolutionary wise man and small lad, Franklin was only 46, while William was not a small boy but a young man of 21.

The experiment led to the development of life-saving lightning rods attached to buildings and secured the international fame of Benjamin Franklin.

But like some mythical curse, despite the familial bonds depicted in the lightning art created decades after the experiment and even after Franklin's death, Benjamin and William were destined for trouble.

Not because of the kite experiment but because of the lightning rod of controversy of being on different sides of the American Revolution.

William was born in 1728 or 1729 from a relationship out of wedlock. Franklin never discussed the identity of William's mother, not even in his famed autobiography, likely for the sake of his son, but he fully claimed William and raised him in his household.

William was born just prior to Franklin marrying Deborah Read Rogers, who would bear Benjamin two more children.

"William became at once a part of the family, and his father doted on him," writes Edmund S. Morgan in his book, "Benjamin Franklin." "... Within his own family (Benjamin) was most obviously and most demonstrably fond of his son William, who became his closest confidant ..."

As a teenager, William accompanied his father on Benjamin's inspections along the Pennsylvania frontier, according to Edwin S. Gaustad in "Benjamin Franklin."

In 1757, when the Pennsylvania Assembly wanted to negotiate taxes and local rights, it sent Franklin to England. Franklin took William, then in his late 20s, with him.

They housed together and sought to fit into English society.

"Franklin and son imitated the fashions of London, buying new clothing, new knee buckles, and appropriate stationary," Gaustad writes. "'Everything about us pretty genteel,' the satisfied father noted."

Father and son traveled to northern England, Scotland and the Netherlands. They watched the coronation of King George III.

Yet, as Franklin worked often with little success in representing more American colonies and negotiating in an increasingly troubled atmosphere for colonial rights, William fit into British life better than his father.

Franklin returned to Pennsylvania. William stayed in England. He married well and was appointed royal governor of New Jersey, a success that would lead to trouble with his father.

For as William became a royal appointee, Franklin began questioning the American connection to Britain.

"A cloud was coming over the horizon, and there was no lightning rod to defuse its emotional charge," Isaacson writes. "The first signs of the tension that would develop between father and son came when Franklin decided to sail from England without him on Aug. 24, 1762 – the very day the news of William's pending appointment appeared in the papers and less than two weeks before his scheduled wedding."

"... Indeed, it meant that William, then about 31, would have a station in life higher than his father's, one that would likely reinforce his son's unattractive tendency to adopt elitist airs and pretenses."

The governorship then the push for American independence set the stage for the eventual split between father and son.

By the 1770s, Franklin had reluctantly then fully embraced being an Independence man. He urged his son to join him in seeking American independence. William refused. He would remain loyal to the king and England and remain the governor of New Jersey.

"Away from his father, (William) had grown into a man of his own, as convinced of the correctness of his principles as his father was of his principles, and as stubborn in defending them," H.W. Brands writes in "The First American." "The apple had fallen close to the tree in regard of character, if not of politics."

William was deemed an enemy of the Revolution. He was arrested "as a virulent enemy to this country, and a person that may prove dangerous." He was taken into custody and placed under the watch of American authorities.

"Franklin lifted no finger on behalf of his son," Brands writes. He sent $60 to William's wife but "he would not forgive William. Steeling his heart, he left him to his fate."

Franklin was angry that his son would not follow him but he also worried that any effort to help William would cause other Founders to question his loyalty to the American cause.

Though a famed publisher and writer, Franklin ceded writing the Declaration of Independence to Thomas Jefferson because he knew some Americans did not trust him because of William's loyalty to England.

Eventually, William would be sent to live the rest of his life in Britain, forever estranged from Franklin and America.

Franklin wrote his son years later.

"Indeed, nothing has ever hurt me so much and affected me with such keen Sensations, as to find myself deserted in my old Age by my only Son, and not only deserted but taking up Arms against me, in a Cause wherein my good Fame, Fortune and Life were all at Stake."

William claimed he had a duty as a royal governor but as Gaustad notes, "Perhaps, Franklin replied, but there was a higher duty than that: of a son to his father."